Europe is Buzzing About AI and Emerging Tech While Also Leading the Fight to Regulate It.

The US Should Take Notes

Talking about artificial intelligence in the Westminister Palace is a hell of a juxtaposition. Nothing about the nearly 200-year-old UNESCO World Heritage site, from its gothic architecture to the traditions carried out in its halls, feels modern or technological. Nonetheless, I found myself there on the second day of a three-week European tour discussing chatbots, AI image generators, and other modern technology with senior members of the UK’s House of Lords.

In fact, AI was the topic of conversation, or at least an undercurrent, in all of my meetings across Europe, from the UK Parliament and Chatham House to the Slovakian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and NATO.

In South London, we spent time with high school students leveraging a debate program to sharpen their skills of reason and communication while the program’s creator is using AI to scale the program to schools around the globe. In Bratislava, we learned that ChatGPT has been used to inform communication at the highest levels of the Slovakian government. In Brussels we learned, unsurprisingly, that NATO views AI and a host of other technologies through the lens of strategic competition, believing that its allied countries need to have better, more sophisticated versions than their geopolitical rivals, such as China.

This is fellowship diaries, a series of dispatches about my travels as a Marshall Memorial Fellow. In 2022, I was privileged to be selected as a Marshall Memorial Fellow (MMF), the flagship leadership program of the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

MMF allows leaders from the United States and Europe to explore each other's political, economic, and social landscapes through delegations on either side of the Atlantic.

Notable alums include Former Georgia State Representative and voting rights activist Stacy Abrams, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, and French President Emmanuel Macron.

For the centerpiece of my fellowship experience, I embarked on a three-week tour through Washington DC, London, Bratislava, Belgrade, and Brussels in September 2023.

I’m documenting my thoughts and learning here.

I found all of this promising. I’ve predicted that every smart organization -- governments, civil society organizations, and companies alike -- will soon be querying internal chatbots to boost productivity. I’ve also warned that the worst thing an organization can do concerning AI is to fail to foster internal experimentation.

In the eleven months since generative artificial intelligence entered the public consciousness, countless companies have moved at breakneck speed to capitalize on it. Meanwhile, governments have been slower in moving to regulate it.

But while Europe is not only buzzing about using AI, they are also leading in regulating it.

There is no better example than the EU AI Act. As the Washington Post reports, in June, “The European Parliament overwhelmingly approved the E.U. AI Act, a sweeping package that aims to protect consumers from potentially dangerous applications of artificial intelligence. Government officials made the move amid concerns that recent advances in the technology could be used to nefarious ends, ushering in surveillance, algorithmically driven discrimination, and prolific misinformation that could upend democracy. E.U. officials are moving much faster than their U.S. counterparts, where discussions about AI have dragged on in Congress despite apocalyptic warnings from even some industry officials.”

While the AI Act itself was less of a conversation in my time there, some of the things it hopes to mitigate, such as the nearly-free production of disinformation content at scale, dominated the concerns of policymakers, executives, and activists we spoke to.

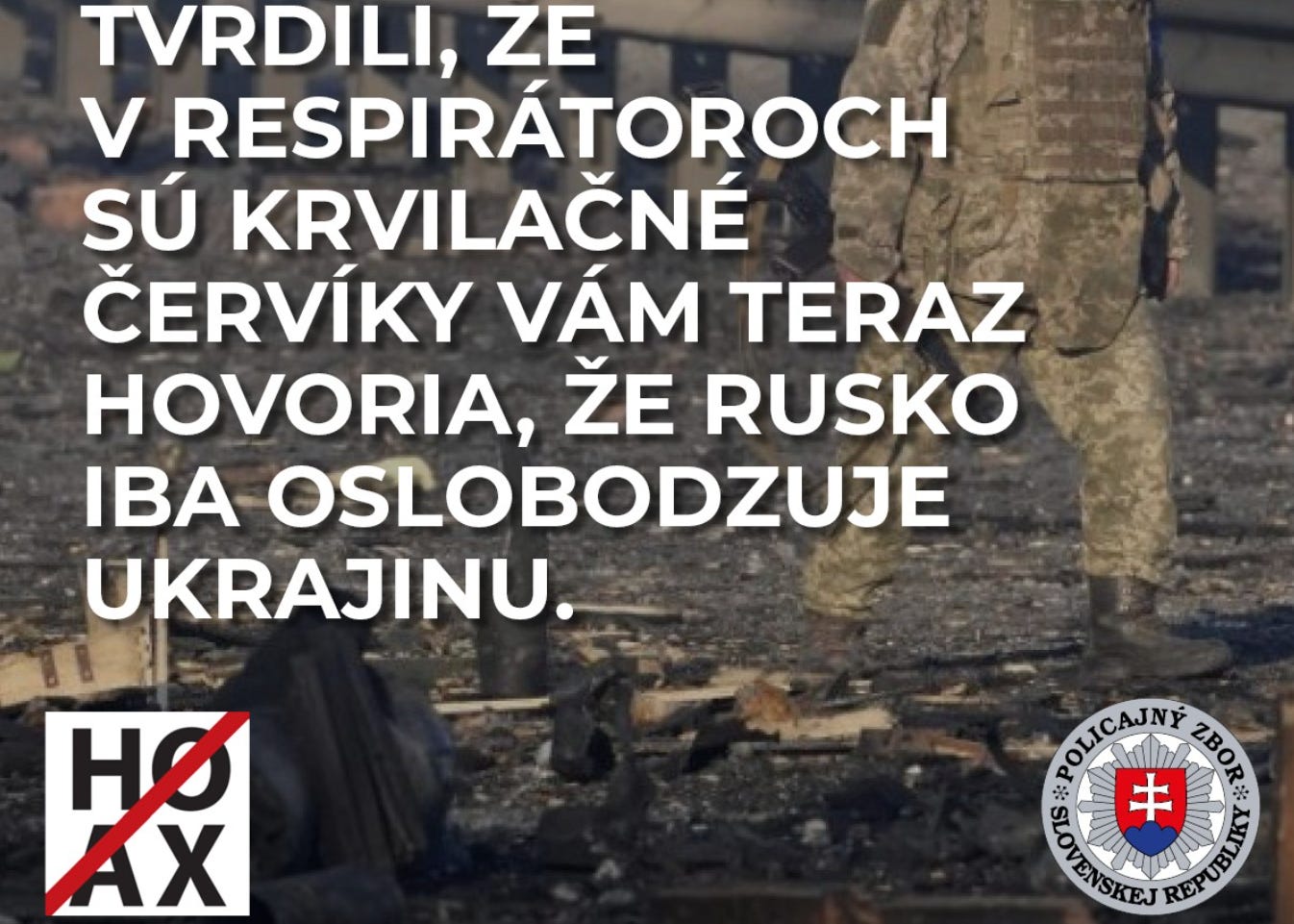

This was no more apparent than in Slovakia, where the country’s campaigns for its national elections, which will be held on September 30th, have been riddled with disinformation spread on platforms like Facebook. We learned of heinous examples in conversations with the people and organizations on the front lines of fighting it. One viral post shared widely on Telegram and Instagram falsely claimed a candidate for Parliament had died from a Covid vaccine. In Bratislava, Slovakia’s capital, officials lamented their inability to influence large tech companies to implement necessary protections to limit the spread of disinformation.

While listening to these stories, I wondered if the EU’s collective regulatory power and competitive advantage as a technology regulator might be the answer. After all, an EU law passed last year just recently pressured Apple, the world’s most valuable company, into changing how its devices are charged across the globe, something that consumers and the marketplace had failed to do alone.

EU lawmakers are way ahead of me. I learned in Brussels that earlier this year, the EU passed a law -- the Digital Services Act -- that went into effect in August and is aimed at decreasing illegal and harmful content, including disinformation. The New York Times reports, “The law defines broad categories of illegal or harmful content, not specific themes or topics. It obliges the companies to, among other things, provide greater protections to users, giving them more information about algorithms that recommend content and allowing them to opt out, and ending advertising targeted at children. It also requires them to submit independent audits and to make public decisions on removing content and other data — steps that experts say would help combat the problem”

The law is a good step towards accountability. Despite being very broad and appearing to lack some of the things I think should be required to fight disinformation, such as disclosure requirements for posters of content beyond just ads, it's far better than anything currently in effect in the US.

Slovakia’s elections will be the first in Europe since the law has gone into effect.