One Lesson from the SVB Crisis: Banking Regulation Needs to be Modernized

More FDIC insurance? Limits on what banks can invest in? Mark to market accounting?

Now that the federal government has saved Silicon Valley Bank’s depositors, the blame games and post-mortems have begun. From my vantage point, one obvious step in improving the banking system is to modernize the regulation that governs it.

Smarter people with more expertise will have better ideas than me, but there are a few things that immediately popped into my mind:

1. Increasing the FDIC Insurance Limit

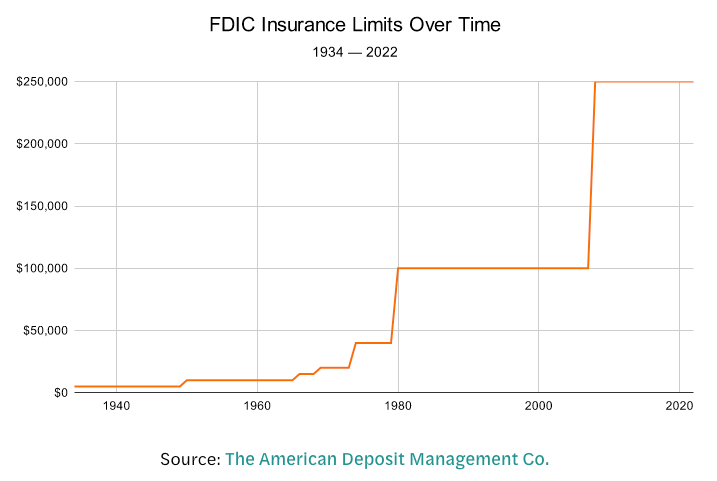

FDIC per deposit insurance limit was created in 1934, during the Great Depression, at $2,500. When I first learned about banking and economics in college, the limit was $100k. Since its inception, it has increased seven times, most recently to $250k in 2008 as part of Dodd-Frank. While it has outpaced inflation, it hasn’t kept pace with the size of the U.S. banking system.

The logic for a $250k limit isn’t perfect. The largest banks -- those that are “too big to fail” -- have implicit government insurance well above $250k. Now, after SVB’s depositors have been made whole, that same implicit insurance may also apply to much smaller banks.

Why not just make all of this more explicit and clear?

2. More Limits on What Banks Can Invest In

SVB was borrowing money on a very short-term basis and lending money on a much longer-term basis. This mismatch in maturities, combined with a rising interest rate-facilitated decline in the value of its assets, precipitated widespread concern about SVB’s solvency.

But SVB wasn’t ignorant of this risk; they were just more greedy than fearful.

Bloomberg reported that “In late 2020, the firm’s asset-liability committee received an internal recommendation to buy shorter-term bonds as more deposits flowed in. That shift would reduce the risk of sizable losses if interest rates quickly rose. But it would have a cost: an estimated $18 million reduction in earnings, with a $36 million hit going forward from there. Executives balked. Instead, the company continued to plow cash into higher-yielding assets.”

When SVB’s deposits jumped to $189 billion in 2021 from $49 billion in 2018 amid a boom in venture capital funding, SVB invested $80 billion of that new liquidity in mortgage-backed securities at an average yield of 1.56%.

Now in the aftermath of its failure, it's reasonable to ask if SVB should have been able to take these sorts of risks in the first place. If the government will eventually save depositors, why not do the saving upfront by limiting the range of investments they can make? If there’s an implicit government guarantee on the way down, why not impose more balance sheet restrictions on the way up?

3. Make Banks Market their Assets to Market

SVB’s troublesome assets were in its “Held-To-Maturity” portfolio. While those assets had declined in market value, bank accounting rules don’t require their balance sheet to reflect that.

Having some requirements for banks to mark their assets to market would require banks to address insolvency risks more proactively. This would likely lead to 1) a slower, more orderly withdrawal of deposits over time, 2) the opportunity for the bank to raise capital to “sure up” its balance sheet, something that SVB was attempting to do in the days and hours before the run that killed it.

New research published this week illustrates that the decline in interest rates is meaningfully affecting the balance sheets of as many as 10 percent of U.S. banks:

We analyze U.S. banks’ asset exposure to a recent rise in the interest rates with implications for financial stability. The U.S. banking system’s market value of assets is $2 trillion lower than suggested by their book value of assets accounting for loan portfolios held to maturity. Marked-to-market bank assets have declined by an average of 10% across all the banks, with the bottom 5th percentile experiencing a decline of 20%.

We illustrate that uninsured leverage (i.e., Uninsured Debt/Assets) is the key to understanding whether these losses would lead to some banks in the U.S. becoming insolvent-- unlike insured depositors, uninsured depositors stand to lose a part of their deposits if the bank fails, potentially giving them incentives to run.

A case study of the recently failed Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) is illustrative. 10 percent of banks have larger unrecognized losses than those at SVB. Nor was SVB the worst capitalized bank, with 10 percent of banks having lower capitalization than SVB. On the other hand, SVB had a disproportional share of uninsured funding: only 1 percent of banks had higher uninsured leverage. Combined, losses and uninsured leverage provide incentives for an SVB uninsured depositor run.

We compute similar incentives for the sample of all U.S. banks. Even if only half of uninsured depositors decide to withdraw, almost 190 banks are at a potential risk of impairment to insured depositors, with potentially $300 billion of insured deposits at risk. If uninsured deposit withdrawals cause even small fire sales, substantially more banks are at risk. Overall, these calculations suggests that recent declines in bank asset values very significantly increased the fragility of the US banking system to uninsured depositor runs.

It takes a tremendous amount of financial sophistication to conduct a competent risk assessment of your bank. If accounting rules force banks to share the market value of their balance sheets, then less sophisticated financial sleuths can more easily see a problem. While companies can hire people to do this, very few people can do it themselves.

But part of the reason the SVB crisis unfolded so quickly is that the market was late to realize the change in SVB’s balance sheet. Investors and depositors were absorbing several months of information in several days, and in doing so, they panicked.

Mark-to-market accounting wouldn’t have changed the composition of SVB’s balance sheet, but it would have changed how and when the market understood it.