You're Bad at Math. That's Bad for Democracy.

When we can't distinguish millions from billions, grasp probability, or understand scale, we become sitting ducks for economic myths, financial scams, and political manipulation.

Hi, I’m Jamaal. Welcome to Jamaal’s Letter, where I share insights, predictions, and strong opinions on the future of markets, work, business, tech, and more.

The people who read this newsletter are the people who run the world. If you aren’t yet a subscriber, consider joining them by subscribing below. Please share it with your friends and colleagues if you find it helpful:

Read time: 5 minutes

I used to think I wasn’t a math person.

One of my earliest school memories is playing a game called "Around the World," where students compete to see who can move around the entire class first by answering quick-fire arithmetic flashcards faster than their classmates. I remember watching other kids shout answers faster than me. I was good at it, but others were better. In my mind, they were the “math kids.” I wasn’t.

Yet, my test scores landed me in my school’s gifted and talented program. I was recommended by a Black teacher who saw my potential. (Research shows Black teachers identify Black gifted students at three times the rate of non-Black teachers, even when test scores are held constant.) I was placed in the highest math tracks by middle school. I still didn’t consider myself a math person, and no one ever told me someone like me was supposed to be good at math.

By college, I was acing calculus tests, blowing through problem sets like puzzle pieces falling into place. Calculus wasn’t subjective. It felt like Neo manipulating the Matrix for the first time. Numbers made sense—and they told stories that words alone couldn’t. Still, I was good at that course, I told myself, but this was University of Missouri-level calculus, not MIT.

Nonetheless, the skills opened doors. I parlayed good math grades into an internship and eventually a job on Wall Street. I was ranked at the top of my investment banking analyst class. I decided to get my MBA. My GMAT quant scores were just good, while my verbal scores were great. My inner narrative: “I’m a word person, not a math one.” I scored well enough to get into Stanford, where some of my classmates were mathematical wizards.

It took me well into my post-MBA career to realize that I am, in fact, “a math person.” While the math I use on a day-to-day basis hasn’t gotten anywhere near as complicated as that college calculus course, having an intuitive understanding of math, statistics, and numbers has been a cornerstone skill throughout my career at the intersection of finance and technology. But more than that, math has shaped my understanding of the world. It’s helped me spot when a politician is cherry-picking crime data to stoke fear, understand the reality of a company touting 300% growth on a tiny base, and ignore a loan “forgiveness” offer that actually front-loads your interest into a longer repayment plan.

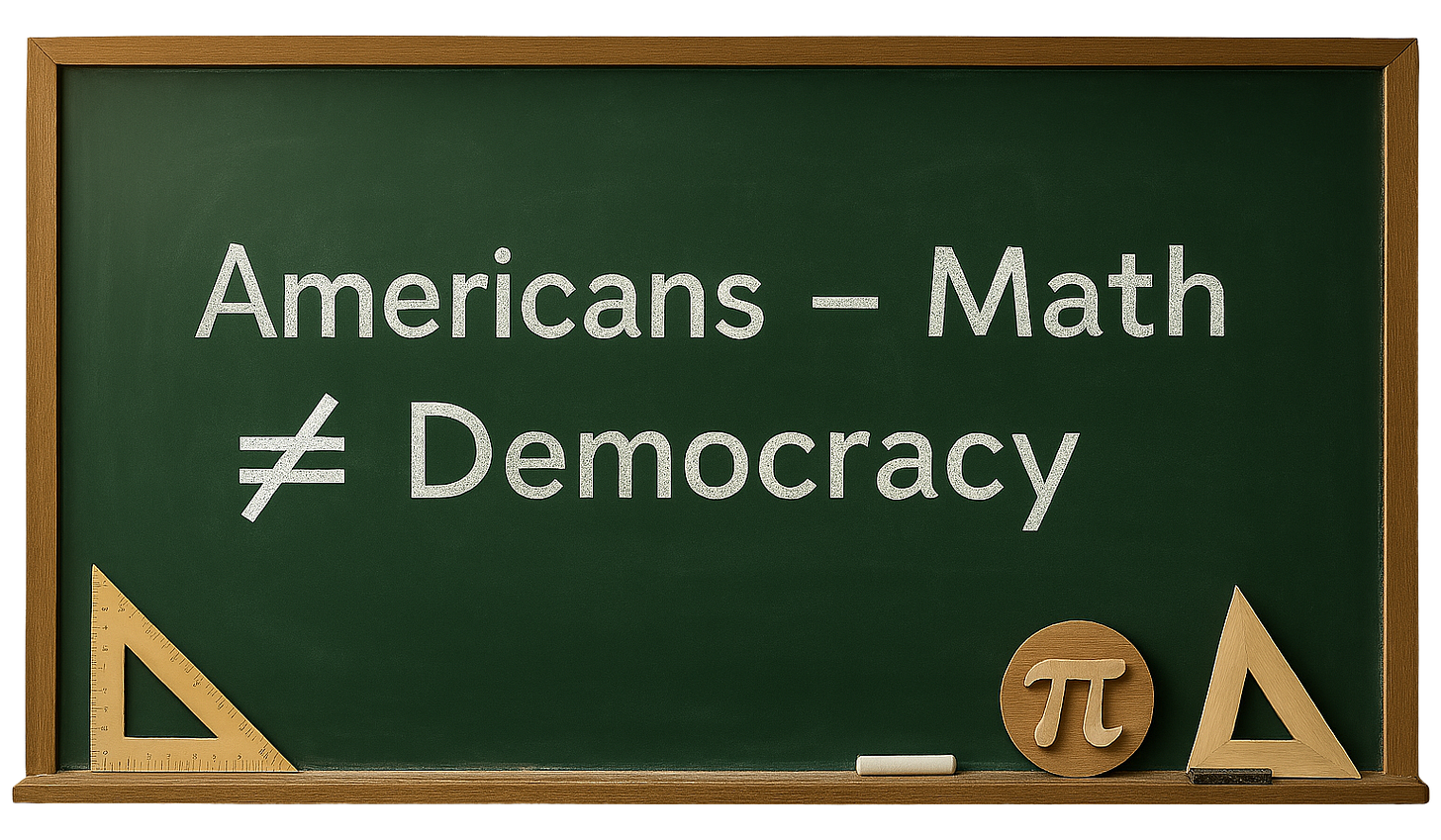

Most Americans don’t share that fluency, or that comfort. And that’s a problem that goes far beyond STEM careers or standardized testing. It’s a democratic liability.

Studies show that parental math anxiety is deeply correlated with children’s math performance. Parents who feel uncomfortable with math often transmit that discomfort, especially when helping with homework. Their kids not only learn less, but they also internalize anxiety. They learn to believe they’re not “math people” either. The negative effects are especially pronounced when anxious parents frequently help with math homework. In those cases, children not only retain less over the year but develop math anxiety of their own. The transmission isn’t just cognitive, it’s emotional. When kids hear adults say things like “I was never good at math,” or see them visibly uncomfortable with numbers, they internalize those signals as fixed traits, not temporary gaps.

Meanwhile, the national picture is bleak. According to the Pew Research Center, U.S. students rank 28th out of 37 OECD countries in math. That’s not a marginal gap, that’s a red flag. In a society awash in data, with endless attempts to influence your votes, purchases, and perceptions, our numerical illiteracy is more than a personal inconvenience; it leaves us vulnerable and defenseless.

Society depends on some of us excelling at math. We need brilliant minds pushing the boundaries of science, engineering, technology, and medicine. Those innovators drive the breakthroughs that power our economy and help solve global challenges. But it’s just as important that all of us have a basic level of competence with math and fluency with numbers. Not so everyone can code or build rockets, but so we can navigate a world flooded with data, percentages, and statistical claims. A national baseline of math literacy isn’t just good for innovation, it’s a civic safeguard. It protects us from being manipulated, misled, or sold a story that falls apart under even the lightest mathematical scrutiny.

You don’t have to look far for evidence.

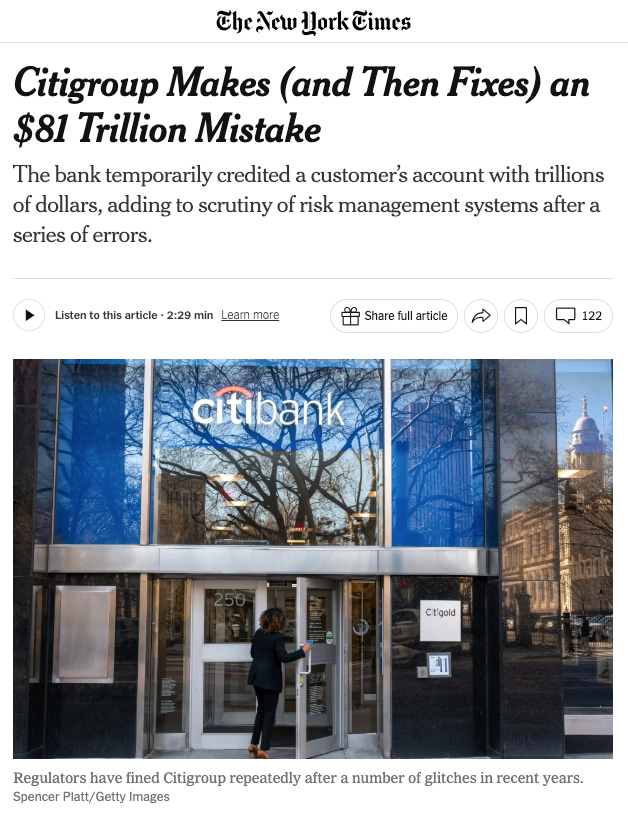

In February, a story about Citigroup "accidentally" transferring $81 trillion to a customer made headlines. Social media exploded with jokes, dreams, and disbelief. Major outlets ran with the headline.

But the entire narrative was absurd. Citigroup’s total deposits are only about $1.3 trillion. The entire U.S. GDP is $28 trillion. The global GDP? Around $110 trillion. In other words, the error wasn’t just unlikely—it was economically impossible. Yet millions of people believed it, shared it, and built stories around it. What should have been an obvious implausibility was treated like a plausible bank flub.

The real story wasn’t Citigroup’s lack of internal controls. It was us.

When we lack numerical intuition — when we don’t know what billions and trillions look like — we’re vulnerable. Vulnerable to economic myths. Vulnerable to financial scams. Vulnerable to the kind of fearmongering or fantasy that bypasses reason because we don’t have the tools to question the scale.

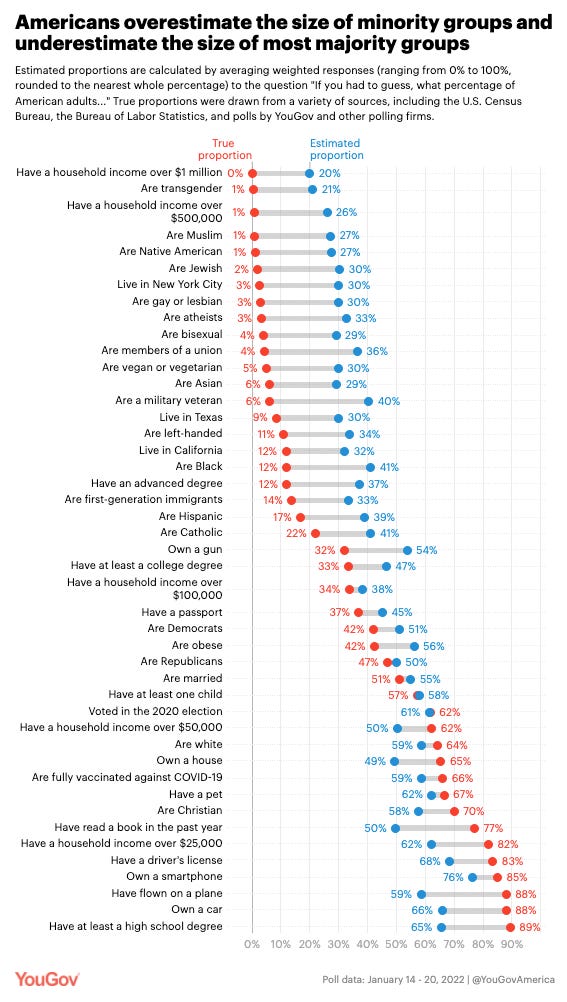

I’m convinced this is why Americans gasp at the $50 billion to $80 billion we spend each year on foreign aid, despite it being roughly 1% of the federal budget, or why we incessantly debate policies that primarily affect such small portions of the population. It distorts our legitimate concerns about wealth inequality, corporate greed, and government corruption.

These public numeracy lapses happen often.

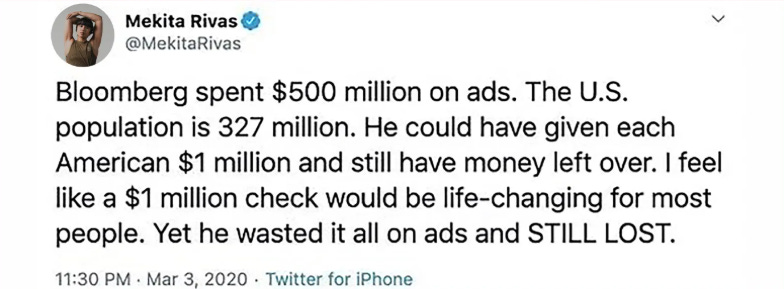

During the 2020 Democratic primary, Michael Bloomberg spent nearly $1 billion on his short-lived presidential campaign. A tweet went viral claiming he could have used half that amount — $500 million — to give every American $1 million. On national TV, MSNBC’s Brian Williams and New York Times editorial board member Mara Gay read the tweet and called it both “true” and “an incredible way of putting it.” Neither of them — by all measures exceptionally accomplished in their fields — paused to consider the math. In reality, Bloomberg’s $500 million, given equally to all Americans, would have yielded approximately $1.53 each.

I remember the episode vividly. Even a simple sense of intuition about large numbers and scale should have raised red flags. The idea that $500 million could yield millions for every American is a clear example of how quickly mathematical intuition can catch errors that even accomplished media figures might overlook.

We all laughed about it afterward. But beneath the meme was a disturbing truth: if some of the country’s most trusted journalists can miss a math error that obvious, what does that say about the electorate?

Our math problem doesn’t just show up in classrooms or test scores. It influences how we interpret campaign promises, evaluate public spending, and decide whom we trust. It shapes how we vote, how we shop, and whether we’re vulnerable to grifters, marketers, or political operatives.

Democracy doesn’t just require informed voters — it requires numerate ones. Voters who can tell the difference between millions and billions, who can ask whether that budget line is big or small in context, who don’t mistake data for truth without understanding what’s being measured, or manipulated.

When I think back to that summer calculus course, I’m grateful, not because I learned how to differentiate functions, but because it was evidence of my evolving ability to think in terms of magnitude, patterns, and probability. I learned how to pause before accepting a number at face value. I learned how to ask questions.

If we want to strengthen democracy, we can’t stop at civics. We need to teach — and value—numeracy. Because when we don’t understand the numbers, someone else will use them against us.

This piece really reframes math not just as a subject, but as a form of civic armor. The connection between numeracy and democracy is so often overlooked — yet it's exactly this kind of intuition about scale, probability, and context that protects us from manipulation. More of this kind of thinking, please.