Seeing the Balkans Beyond Movie Stereotypes

Tall people, cosmopolitan but not global vibes, violent tv, and no one wants to talk about Kosovo

Before September, I’d only ever once been farther East in Europe than Germany. Most of my perceptions of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe had come from movies, typically U.S. action movies portraying some “American” hero -- think Jason Bourne -- traversing narrow streets or dark, crowded nightclubs chasing or being chased by assassins.

When I landed in Belgrade as the third stop of my three-week European tour, I was excited to see this part of Europe beyond Western film stereotypes and intrigued to explore a region that has spent roughly 15 of the last 100 years fighting literal wars. I have childhood memories of adult discussions and news reports referencing places like Yugoslavia -- the Central and Southeastern European nation that encompassed many of the region’s now-separate countries for more than 70 years ending in 1992 -- and people like Slobodan Milosevic -- the former President of Yugoslavia who died while on trial for war crimes.

Serbia is a stark reminder that part of “American” privilege is rarely being in places where bombs have fallen during your lifetime as part of an international conflict between nation-states.

In my short time in Serbia, here’s what stood out:

Serbs are tall

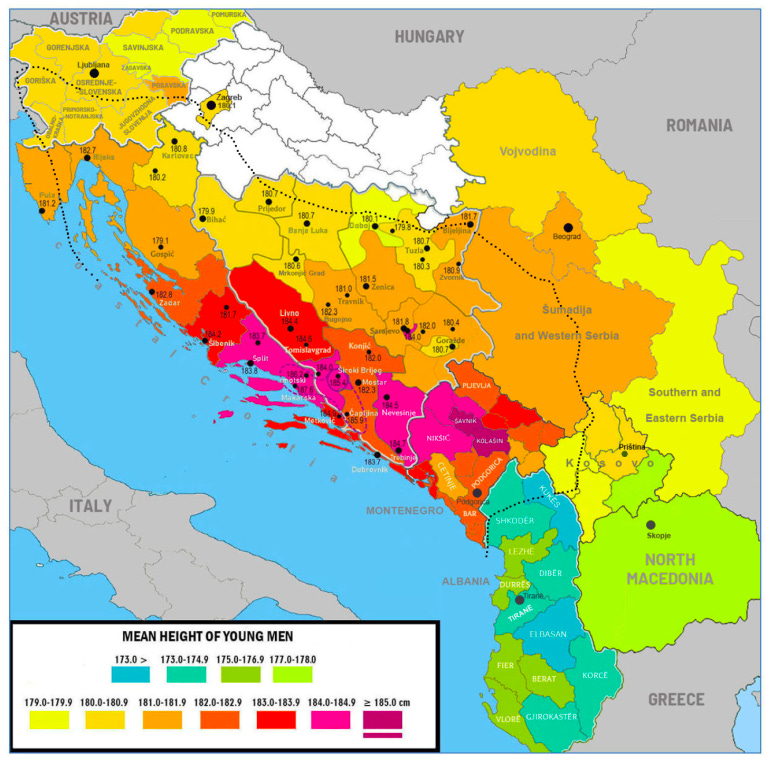

At 6’3” (191 cm), I rarely feel short. I’ve been to the Netherlands, long considered the world’s tallest country, but never more than in Serbia has my height felt so average. It was common to see large groups of young men all 6’6” (199 cm) or taller, and I saw at least a few 7-footers (213 cm+) per day. The average Serbian man is 5’11”(180 cm), and what I came to realize was that Serbia’s population is the fourth tallest on earth, after only The Netherlands, Denmark, nearby Montenegro, and Norway. In fact, the people of the Dinaric Alps -- the mountain range that separates the Balkan Peninsula from the Adriatic Sea and passes through countries that include Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, and Montenegro -- are some of the tallest in the world.

Cosmopolitan But Not Truly Global Vibes

Within minutes on the ground in central Belgrade, I felt like I was in one of the most cosmopolitan places I had ever been. Extremely lively and walkable at its core, its streets were lined with shops and cafes where young Serbs smoked, drank, and ate.

I’d been told beforehand that Belgrade was a party city. While I failed to make it to, one of the city’s floating barge parties on the Danube River, known as splavovi, I did find myself in a Belgrade nightclub packed tightly alongside younger Serbs who were all singing along to popular electronic-infused Balkan folk music.

But during the day and night, Belgrade was missing some of the trappings of a genuinely global, cosmopolitan city. Upon arrival at Nikola Tesla airport, we realized that Belgrade doesn’t have Uber -- a nearly ubiquitous and essential luxury in countries where I don’t speak the local language. Instead, its dominant mobile ride-sharing apps -- for foreigners at least -- were riddled with user-interface issues, virtually unusable, or allowed you to call a car but still required you to pay for the ride outside the app.

Yet, for all of Belgrade’s feelings of modernity, it also lacked a staple of a modern, future-oriented city -- bikes. In four days in the city center and adjacent commercial and residential neighborhoods, I saw virtually zero bikers who weren’t delivery workers, no bicycle commuters, and almost no one biking for exercise. Perhaps I missed its most bike-friendly areas, but this lack of cyclists and cycling infrastructure in the city’s most densely packed areas illustrates that Belgrade won't be showing up on any “best places to bike” lists on the world's most bike-friendly continent.

Violent Reality TV

In the offices of CRTA, the Center for Research, Transparency and Accountability -- a Serbian nonprofit advocating for democratic culture and civic activism -- we had a rousing debate about the relative roles of media in the US and Serbia.

While the US’s largest media entities are corporate-owned, Serbia’s media giants are directly or indirectly controlled by its government. In recent years, the country has been plagued by an insidious version of a great American export -- reality television. When Serbs told me of the violence on their reality shows, I argued that the US was no different. I was wrong. In Big Brother-style reality shows that air for hours, viewers routinely watch war criminals as cast members and extreme violence against women. “In 2021, around a dozen cast members watched impassively while a convicted felon strangled a woman unconscious on the show Zadruga -- one of the most popular reality series in the Balkan country.” This violent programming has received increased scrutiny this year for contributing to a culture of violence blamed partly for a pair of back-to-back mass shootings in May that rocked a nation “scarred by wars, but unused to mass murders.”

The above video is a compilation of fights from Serbian reality television shows.

Kosovo: Talking Points and Hushed Tones

The most sensitive topic was Kosovo -- the landlocked territory in the Balkan Peninsula that declared independence from Serbia in 2008 after a war and decades of ethnic and political tensions.

The Kosovo war -- a brutal affair resulting in more than 11,000 deaths -- pit government forces from the then Federal Republic of Yugoslavia against the Kosovo Liberation Army from February of 1998 to June 1999, culminating in the end of a NATO bombing campaign, a UN resolution, and a NATO-led peacekeeping force. Our hotel was within walking distance from locations where NATO bombs had fallen in the Spring of 1999.

The topic of Kosovo -- from the historical record to modern-day relations -- came up in official meetings and during unofficial conversations, usually in inconspicuously similar talking points or hushed tones. The wounds of that conflict appear to be far from healed. On one of our last days there, a group of heavily armed ethnic Serb gunmen ambushed a police patrol in northern Kosovo. The attack killed one Kosovar police officer and wounded two others. Three of the gunmen were eventually killed. The attack was some of the worst violence between Serbia and Kosovo in years and came amid a broader EU effort to normalize relations between the two countries.

Generally, Kosovo felt like something that many Serbs weren’t comfortable discussing.

Intrigued by its tabooness, I hoped to fly the ~150 miles (~240 km) from Belgrade to Kosovo one meeting-free day, only to learn that there are no direct flights from the Serbian capital to any city in Kosovo. The direct air route hasn’t existed since the war. To get to Pristina, Kosovo’s capital and largest city, I would have had to fly from Belgrade outside Serbia and stop in Vienna, one of a handful of potential layovers. With the only alternative being a six-hour bus route, I did not go.

A “Flawed Democracy”

Most of all, Belgrade felt like the capital of a country with so much potential, stunted by a recent history of conflict. In meetings across civil society organizations, experts on a range of topics described the country as poor and described a mixed relationship with democracy. At ~$23,000, Serbia’s per capita GDP, at purchasing power parity, is roughly 66th globally, behind the Maldives and just ahead of Libya.

In The Economist’s 2022 Democracy Index, Serbia ranks as the world’s 68th most democratic country, in the “flawed democracy” category, alongside 15 other countries in “Eastern Europe”, a region that includes no “full democracies,” the most democratic category. Serbia, alongside many of its neighbors, ranks particularly low in “political culture,” the index’s term to describe things like social cohesion, political consensus, and media politicization. While Serbia doesn’t rank as low regarding civil liberties, I was shocked to learn of the harshness of the country’s COVID lockdowns, which included nightly and weekend-long curfews that led to protests and violent clashes with police.

This is fellowship diaries, a series of dispatches about my travels as a Marshall Memorial Fellow. In 2022, I was privileged to be selected as a Marshall Memorial Fellow (MMF), the flagship leadership program of the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

MMF allows leaders from the United States and Europe to explore each other's political, economic, and social landscapes through delegations on either side of the Atlantic.

Notable alums include Former Georgia State Representative and voting rights activist Stacy Abrams and French President Emmanuel Macron.

For the centerpiece of my fellowship experience, I embarked on a three-week tour through Washington DC, London, Bratislava, Belgrade, and Brussels in September 2023.

I’m documenting my thoughts and learning here. See below for other dispatches in this series.